No time to read? Listen instead.

We’re trying something new. People frequently tell us they would rather listen to books than read them. They’ve also asked that Ian read them. So, we are making recordings of Ian reading his books available, at no charge.

The first book is our best-seller, XIV: How the Fourteenth Amendment Ate the First.

Comment on this post to let us know what you think, and if you have any particular BMBooks you’d like to hear.

Please share this post with your friends.

Is that news or gnos?

This morning I am seeing reports that Kash Patel will be named as acting head of the ATF. When? Oh, sometime next week. Probably.

I think that would be a good thing, but as someone used to say, I’ll believe it when I see it.

It reminded me that for a while now, it’s bothered me that the name news is too often applied, not to reports of what has happened, but to predictions of what will happen.

Those are very different kinds of things, and we need different names to be able to tell them apart.

As Confucius noted, the first step towards wisdom is to call things by their right names.

(It’s a little like when Obama was given a Nobel Prize because it was hoped that he would do something to earn it. So it should have been called something like the Nobel Peace Prompt, rather than the Nobel Peace Prize.)

I’m going to suggest that we use the word news to describe events in the present or immediate past, while using the word gnos (sounds like ‘knows’, short for ‘prognostication’) to describe what a writer predicts will happen in the near future.

For example, reports that Kash Patel has been confirmed as head of the FBI would be news, so you can file that fact away in your head as information; while reports that Kash Patel will be named acting head of ATF would be gnos, so you can assign that prediction the same level of confidence that you would give to stock tips and horoscopes.

Is there a better word than gnos? Perhaps. Probably. I’m certainly open to suggestion. But we need to have some word, to help people distinguish between fact and fiction. The modern world is confusing enough as it is, without inviting news outlets to report on what may be, unencumbered by what has been.

Check out BareMinimumBooks.com.

When only some of us win, all of us lose

Judy Aron's regular posts about what is going on in the House are informative, insightful, well-written, and worth reading. Near the beginning of a recent post, she started out with this comment:

We knew the 23 bills we had before us were going to yield some very good wins.

I don't think that's an unusual sentiment, but it struck me that this attitude — that one side should win while the other side loses — is what creates almost all of the dysfunction that we find in government.

Try the following thought experiment.

Imagine that no bill could pass out of either the House or the Senate without being approved by 95% of its entire membership, rather than by a majority whichever members happen to show up on a given day.

(Also, imagine that every statute sunsets after a short time, so all laws would get regularly reviewed for continued relevance, and updated to reflect changing conditions.)

This would prevent any group of people that is significantly smaller than everyone from depriving everyone else of the government by consent that they were promised in the Declaration of Independence.

Hardly any laws would get passed, but the ones that do wouldn't involve one group insisting that its values should be substituted for the values of substantial groups of citizens who disagree with them.

Because nothing would be enacted without nearly universal support, the law would become ‘something I willingly agree to obey’, rather than what it is now — 'something imposed on me, that I'll ignore or subvert whenever I can'.

Which system would you rather live under — the one I'm describing, or the one that we have now?

Under the current system, majority rule is used as a kind of club, which one 'side' can use to beat up the other 'side', until the other side gains control of the club and returns the favor.

What I'm suggesting is actually pretty simple. It's that instead of always asking,

How many people should we need to get what we want?

we start asking instead,

How many people are we willing to screw over, to get what we want?

As I explain here, when only some of us win, we all lose in the long run.

King Andru’s Magic Mirror

Once there was a kingdom called New Hampshire, which was having an educational crisis.

Well, crisis may not be the right word. A crisis is something that happens suddenly. This was more like a situation, which had been going on for decades.

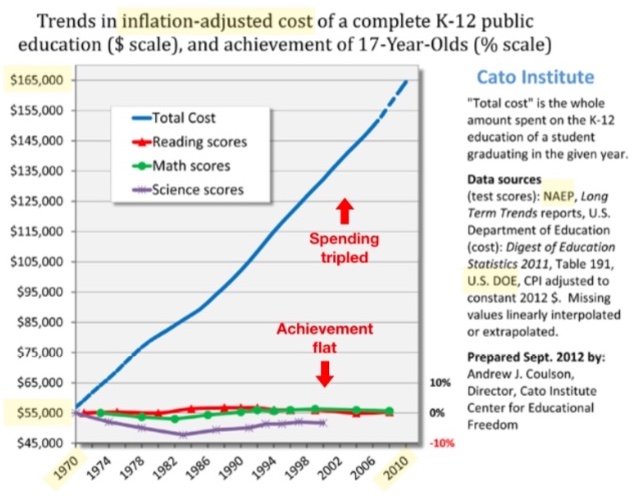

The problem was that, even though the amount of money that the people paid for their schools kept increasing much faster than the costs of other things, student achievement remained unchanged.

Which is to say, it remained pretty lousy. Fewer than half of students could read or do math at the levels of proficiency required to participate in the political, social, and economic systems of a free government.

The king of New Hampshire, Andru the First, constantly had to look for ways to distract parents and taxpayers from this situation. In his chambers, he had a magic mirror that would answer his questions.

One day, he asked, "Magic mirror on the wall, how can I keep my subjects from asking inconvenient and embarrassing questions about student performance?"

"That's easy," the mirror replied. "Get them to obsess about money instead. If they stopped to think about it, they would see that there is no connection between what gets spent and what gets learned. So don't let them stop to think about it," the mirror said.

"How can I do that?" the king asked.

"Persuade them to fight about fairness in how they're being taxed, so they won't have time to think about the quality of the education they're paying for but not getting. Just always remember that even the right answer to the wrong question is still wrong, and that where schools are concerned, any question about money is the wrong question," the mirror said.

So the king followed the mirror's advice. He traveled around the kingdom, proposing different schemes for raising money for schools. Each of these schemes pitted groups of citizens against each other: Citizens with more expensive homes against those with less expensive homes; citizens with higher incomes against those with lower incomes; citizens with children against citizens with no children; and so on.

So the citizens of the kingdom continued to argue over money, a subject that divided them. They never did get around to discussing the subjects that could have united them: What schools should be doing, and why, and how. Eventually, the kingdom fell into bankruptcy -- financial, intellectual, and moral.

But the king — whose own children had been educated in private schools — fled with his family, his personal fortune, and his magic mirror, to another land, where he could find more people that he could “help”.

The Great Volinsky

Once there was a magician named the Great Volinsky. He bragged that he could fool anyone about anything.

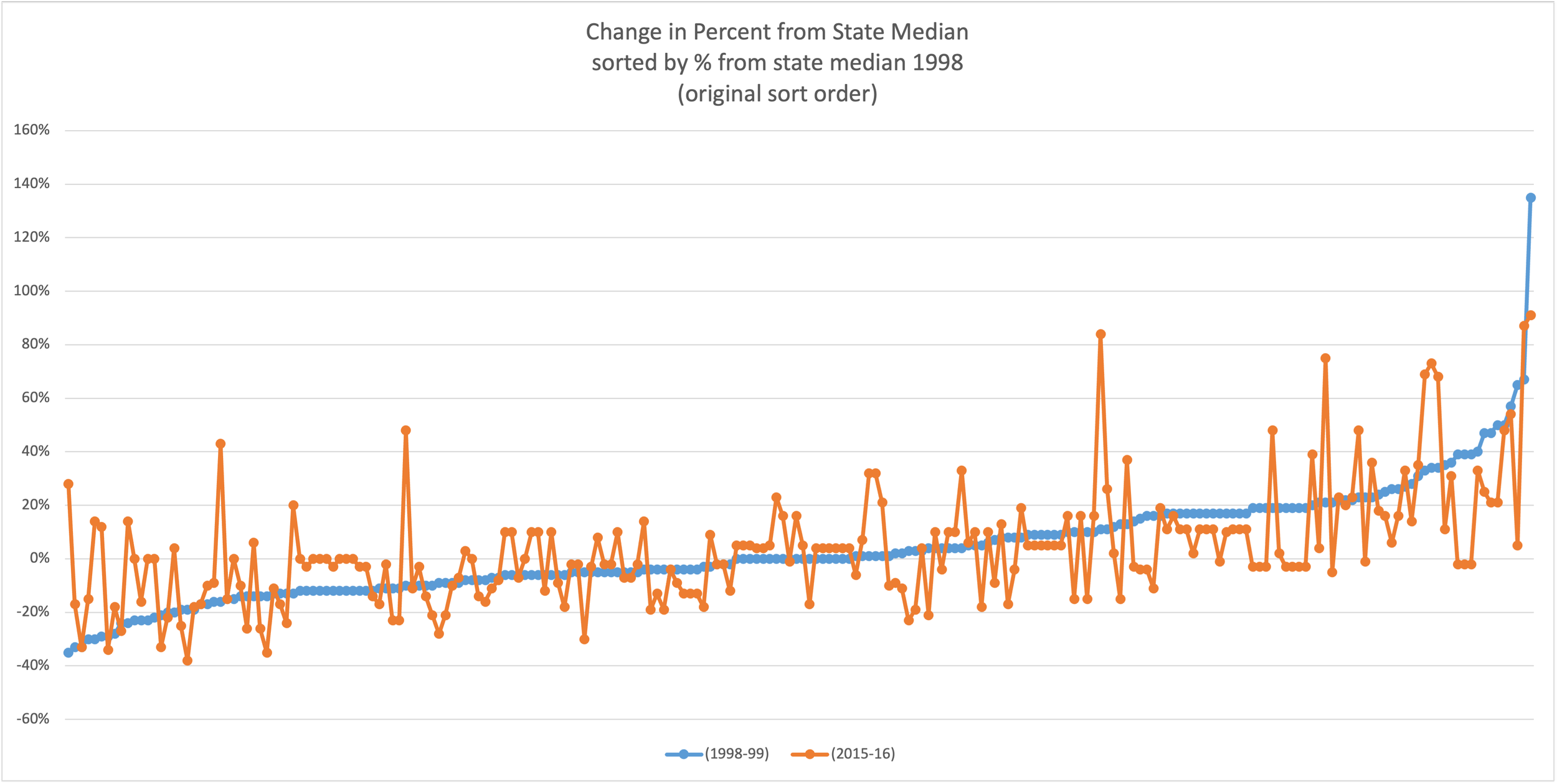

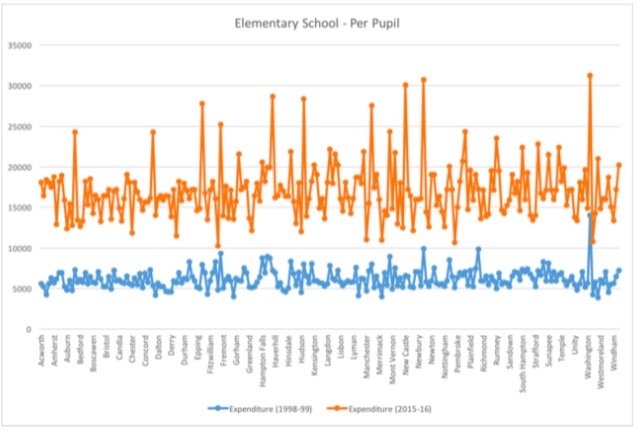

One day in 2017, someone in the audience at one of his performances held up a chart. It showed very clearly that every school district in his state (New Hampshire) was spending more than any school district had been spending nearly two decades earlier (adjusted for inflation), even as student achievement had remained flat.

He asked why this should be the case. Shouldn't more money lead to better education outcomes?

The Great Volinsky said that spending hadn't significantly changed, and that he could demonstrate this. He asked for the data that had been used to make the chart.

First, he calculated the median value for each of the years, 1998 and 2015, separately. He then substituted actual spending for percentage above or below the median, and he sorted the entire chart by the 1998 values. Now the chart looked like this:

Finally, he sorted only the upper line by the 2015 values. Now the chart looked like this*:

* This is the actual chart presented by Andru Volinsky and the School Funding Fairness Project in 2018. More info can be found here.

Of course, now the points that are vertically aligned are from different districts:

So all this chart really showed is that in any given year, some school districts spend more than the median, and some spend less. Which is just the definition of a median.

But the audience was impressed. They ooohed and aaahed and thanked the Great Volinsky for setting their minds at ease. Achievement hadn't increased because spending hadn't changed.

But the Great Volinsky had performed an even more magnificent trick at the New Hampshire state supreme court.

In that case, the judges held up a constitutional article that said (1) legislators should 'cherish' both seminaries and public schools, (2) the people have an inherent and essential right to free and fair competition in the trades and industries, and (3) the state has a duty to protect the people from all monopolies and conspiracies that would hinder or destroy that competition.

No one had any idea what 'cherish' might mean, but it was clear that the state was prohibited from funding, regulating, or operating seminaries, so it seemed clear that it couldn't do any of those things for public schools, either.

But by the time he was done, the Great Volinsky had convinced the court that the state had a duty to fund, regulate, and operate a public-school monopoly that would destroy competition in education.

Now, having seen a little about how he works, how do you suppose he did that?

New Hampshire’s Twenty Billion Dollar Man

Near the beginning of the century, Andru Volinsky persuaded the New Hampshire state supreme court to turn Article 83 of the New Hampshire state constitution on its head [1]. The result? Every school district in the state is now spending more per student per year than any district (except Waterville Valley) was spending before that. Today it is averaging at least $10,000 more per student. And that’s adjusted for inflation.

Today, every district in New Hampshire spends like a rich district.

During this time, we have seen no measurable increases in student achievement. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, since Volinsky’s entire crusade was, and is now, to pursue equality of spending instead of quality of results.

That is, he ignores what might be the two most fundamental questions that need to be considered in any serious discussion of education and schooling (which, we must always remember, are two very different things).

First, if a student wants to learn, who can stop him? (No one.) And how much should it cost to educate a motivated student? (Once he can read, almost nothing.)

Second, if a student doesn’t want to learn, who can make him? (No one.) And how much would it cost to educate a student against his will? (There isn’t enough money in the world.)

There are currently about 160,000 students in New Hampshire tax-funded schools [2]. Multiply that by $10,000 per student, and it comes to at least $1.6 billion dollars per year. (Keep in mind that these are the most conservative possible estimates.) That’s the extra amount that we’re paying each year for nothing, except to boost Volinsky’s ego.

It’s left as an exercise to the reader to calculate the total cost of this debacle over the nearly three decades that have passed since the Claremont decisions were handed down. But even a conservative estimate puts it at over $20 billion. [3]

People who read and listen to what Volinsky is now saying should ask themselves: If this is the cost of his previous crusade (billions of dollars in school spending, in exchange for no increases in results), can we really afford his next crusade?

[1] Article 83, Part 2 says a lot of things. One thing it says is that the legislature must ‘cherish’ both seminaries and public schools. This term has never been defined in any court decision, statute, or regulation. But it’s clear that the legislature can’t fund, operate, or regulate a seminary. So the plain language of the document forbids it from doing any of these things for public schools. Another thing it says is that the state has a duty to protect the inherent and essential right of the people to free and fair competition from all monopolies or conspiracies that would hinder or destroy it. Volinsky and the court agreed that this means: It is the duty of the state to fund, operate, and regulate a monopoly to destroy competition in education.

[2] I use the more accurate term tax-funded school rather than the more commonly used term public school. These schools are not public, in the sense that something like a public park or a public thoroughfare or a public accommodation is. In a true public school, any person, of any age, who lives anywhere, could attend the school. Perhaps more importantly, any person who does not want to be in the school – for example, a teenager who feels his time would be better spent in other pursuits — would be free to leave.

[3] Over that time, enrollment has dropped from well over 200,000 students, while both per-student spending and total spending has continued to increase. A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation would put the total figure at 25 years times $5000 per student per year times 180,000 students, which comes to roughly $22.5 billion dollars. Again, that’s adjusted for inflation. It just reflects the increases resulting from Claremont, not total spending. And the actual amount would be much larger.

Mr. Volinsky's Grocery Store

One day, Pat and Chris came to do some shopping at Mr. Volinsky's Grocery Store. Each of them bought the same items: a loaf of bread, two steaks, three apples, and a gallon of milk.

When they got to the checkout counter, Mr. Volinsky rang up Pat's items, and said that his total came to $40. Pat paid, and went on his way.

When Mr. Volinsky rang up Chris's items, Chris already had $40 out, ready to pay. But Mr. Volinsky said that his total came to $80, twice as much as Pat's total.

"Why should I pay twice as much for exactly the same thing?" asked Chris.

"Because your house is worth twice as much as Pat's house," said Mr. Volinsky.

"But that makes no sense at all," said Chris. "It's not like my house is an ATM, from which I can just withdraw money."

"That's how you pay for schools, isn't it?" said Mr. Volinsky.

Mr. Volinksy has a point, doesn't he? But if this is a good idea — if people who have more valuable homes, or higher incomes, should pay more for the exact same goods and services — then why should we do it only for schools? Why shouldn't people who have more pay more for everything — groceries, meals in restaurants, movie tickets, clothing, gasoline, and so on?

On the other hand, if it's a bad idea, then maybe we should stop paying for schools this way.

Would you shop at Mr. Volinsky's store? Unfortunately, if you're buying schooling for the kids in your town, you're already a customer.

Wouldn't you like to have some other options? Consider that the next time you vote. Ask any candidate whether he believes, as a matter of principle, that people who have more should pay more. If he says yes, then move on to other candidates. But if he says no, ask if he'll work to stop funding schools that way.

Santayana Warned Us About Volinsky

A few sentences into his recent piece in InDepthNH (and other places), Andru Volinsky demonstrates that he has no idea how the statewide education tax actually works, let alone how it should work.

First, no one gets excused from paying anything. Every district collects the full SWEPT tax, spends it on adequacy, and applies any overage toward other district expenses which reduces the non-SWEPT school tax rate. If there is a shortage instead of an overage, that is made up from the state’s Education Trust Fund.

Second, what should matter is the amount that someone gets taxed, not the percentage of his house value that the amount represents — unless the idea is that someone’s house can be treated as a sort of ATM, from which school taxes can be withdrawn. (Of course, every homeowner knows that this isn’t the case, but if it were the case, then it would make sense to tax the owner’s equity in his house, rather than the value of the house. Otherwise, you’re taxing him on money he’s borrowed.)

It’s worth noting that the idea that if two people are paying for the same thing, the one who happens to have more should pay more, is the essence of Marxism. It’s hard to think of an idea that more directly conflicts with the ideals upon which America was founded, and upon which our constitutions are based.

If you doubt this, imagine that two people go to the grocery store, and check out with exactly the same items. The first person is told he has to pay $50, while the second is told he has to pay $100 because his house is worth twice as much as the first person’s. I’ve yet to meet anyone who thinks this would make sense, but it’s exactly how school taxes work. Also vehicle taxes, and income taxes, and any taxes that involve calculating a percentage.

This is all explained in a series of articles starting with this one.

Just a few sentences later, Volinsky again demonstrates his ignorance — or perhaps his willingness to deceive — by completely mischaracterizing what happened in Croydon. There was no ‘stealth’ and nothing was ‘stripped’. The people of the district were persuaded, by open discussion during the course of a completely typical annual meeting, to replace the usual ransom (i.e., the amount demanded by the school board) with a budget (i.e., an amount offered by the voters). This had nothing to do with the Free State Project. In fact, if the three Free Staters at the meeting had left the room before the vote, the amended warrant would still have passed.

If you would like to know what actually happened in Croydon, you should read The Croydon Budget Battle.

In claiming that Free Staters ‘hide their intentions and allegiances’ by running as Republicans, Volinsky doesn’t seem to realize that if you go back and look at the Republican Party platforms since the creation of the party in the 1850s, it becomes clear that the beliefs of Free Staters (and libertarians in general) are much closer to the stated goals of the party — preserving the ideals of the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights — than the beliefs of those who usually run as Republicans. As libertarians, Free Staters are the Indigenous Republicans. If a Free Stater is not a Republican, then neither were Eisenhower or Reagan.

As a character in a story by J.D. Salinger once said of his mother, after a certain point, it’s impolite to go on listening to what he has to say. But it’s deliciously ironic that he chooses to quote Santayana, that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

Let’s look at the recent past. Since the Claremont decisions — in which Volinsky played a major part — school districts in New Hampshire are spending, on average, $15,000 more per student than they were before those decisions. That’s adjusted for inflation. For more than 150,000 students, that comes to more than $2 billion in extra spending every year.

In fact, every district in the state is spending more — again, adjusted for inflation — than any district (except Waterville Valley) was before Claremont. In terms of spending, every district is acting like a rich district, and has been for some time now.

And what do we have to show for it? Over that same period, there has been no measurable increase in student achievement.

So we’re spending an extra two billion dollars each year for nothing. That’s what we got for listening to Volinsky the last time around. (To learn a little more about how that played out, see The School Funding Shell Game).

Let’s take his advice, and not repeat that mistake.

Open Letter to Frank Edelblut and Drew Cline

I've been reading — or trying to read — the 139-page document that is currently out for public review, which identifies proposed changes to the rules promulgated by the state Department of Education.

I believe that the goal of the document is to improve the performance of students in public schools. However, the form, structure, and content of the document more or less guarantee that this goal will not be met.

Dear Commissioner Edelblut and Chairman Cline,

I've been reading — or trying to read — the 139-page document that is currently out for public review, which identifies proposed changes to the rules promulgated by the state Department of Education.

I believe that the goal of the document is to improve the performance of students in public schools. However, the form, structure, and content of the document more or less guarantee that this goal will not be met.

The first major problem with the document is its length: It's 139 pages. There is a well-known technique in civil lawsuits, for foiling the normal discovery process by providing so many documents that the ones that will be useful to the opposing side will probably never be found. That seems to be what's happening here. There are so many changes — and so many rules that might be changed — that there's no way to know which ones are important, and which ones are trivial, without plowing through the whole thing, which almost no one will have the time, motivation, or stamina to do.

The second major problem with the document is its level of detail. It's common knowledge among software engineers that every time you try to fix a bug in a system, you end up creating at least two more. The same is true in statutes and regulations. The solution isn't to keep patching things, but to go back to the original design, the architecture, so that fewer bugs can arise in the first place. The solution is to reduce the need for particular complications by reducing overall complexity.

In the case of public schools, the underlying source of complexity is that the system is time-based, instead of results-based. In any other industry, the goal would be to get students to the finish line as quickly as possible, for as little money as possible. (Of course, this would require knowing where the finish line is, something that requires a shared agreement among students, parents, schools, and taxpayers about where it is. As far as I've been able to tell, no such agreement exists, and no steps have been taken toward reaching one.)

But in the industry of education — or more precisely, the industry of schooling — kids are kept in school for an arbitrary number of years, whether they want to be there or not, and whether they need to be there or not. Once they are there, it becomes necessary to find something for them to do, some way to fill their time, and some way to keep them pacified.

If this were to change — if there were a clear and adequate definition of an adequate education that focused on the desired end state rather than on particular paths to reach it — then many of the problems that the document seeks to address would simply not exist, and the document itself could be reduced to perhaps five to ten pages, and written in clear English rather than in legalese.

Note that in technical fields, a 'standard' says what needs to happen, not how it needs to happen. If you're supposed to produce USB cables, there are some behaviors that the cables have to exhibit, and some tests that they have to pass, in order to meet the standard. How you set up your factory, and what manufacturing processes you use to make the cables, and how long you take to make them, are your business.

Imagine a USB standard that says: The people making your cables have to spend a certain number of hours in training, and your factory has to run for a certain number of hours per day, a certain number of days per year. And we'll certify whatever you produce as a USB cable.

That's the kind of standard we have now for graduating from the public school system, as embodied by documents like this one.

A reasonable standard for graduation would say: This is what we mean by an adequately educated student. Here are the tests he can pass, the skills he can demonstrate, the kinds of problems he can solve.

A reasonable standard would be precise. It wouldn't include pseudo-competencies like 'Use digital tools to develop cognitive proficiency in literacy, numeracy, problem solving, decision making, and spatial/visual literacy’.

A reasonable standard would be consistent. If a certain kind of thinking or problem solving ability is necessary, it would be spelled out, and every student would need to be able to demonstrate it in order to graduate.

If every graduate needs to be able to do things like 'appreciate art', or 'use technology', or whatever, then have tests that let students demonstrate those things; and make everyone pass those tests.

To the extent that the state has a job here — and the written state constitution, as opposed to the oral one, suggests that it does not — that job is to say what product is acceptable, not what process must be followed to produce it. Micro-management guarantees macro-failure, which is what we have now. Focusing on process creates the situation that allows (and to some extent, even encourages) administrators and teachers to ignore (and in some cases, undermine) product.

I suspect that both of you are familiar with the book The Goal, by Eliyahu Goldratt, but if you aren't, I would ask you to read it, since it perfectly captures the situation in which our public school system finds itself, and suggests a way to deal with that situation. Briefly, Goldratt points out that when running any kind of enterprise, every possible action that might be taken needs to be evaluated, not in terms of what invented internal benchmarks it might meet, but in terms of the primary goal of the enterprise. In the case of a business, that goal is to make money. In the case of a public school system, that goal is to produce educated citizens.

Finally, unlike a manufacturing standard, an educational standard needs to be centered on two fundamental concepts: priority and autonomy.

By priority, I just mean that some things are more fundamental than others, and must be dealt with first. If you’re in a course on American history, but your reading skills are below proficiency, then you should be working on reading instead of listening to someone explain history to you. If you’re not rock solid on your arithmetic skills, you certainly shouldn’t be taking algebra… but you also shouldn’t be taking courses in, say, fashion merchandising.

By independence, I just mean that the single most important thing that you should be learning is how to direct your own learning, how to become your own teacher, so that you can learn whatever you want to later on. Nothing else even approaches this in importance.

Any educational standard that isn’t just a wish list must require students to develop foundational skills first, and then require them to leverage those skills to learn to teach themselves. By the time a student is ready to graduate, his teachers should be acting mostly in an advisory role.

To put that a different way: No matter how much a student knows at a given moment, if he’s still depending on his teachers to learn new material, then he’s not ready to graduate.

The third major problem with the document is, in fact, its complete lack of any priority among its requirements. It's like a building code that goes into detail about how to choose the finishes on bathroom fixtures, while ignoring how to tell if the foundation is solid.

Two egregious, and illustrative, examples of this are requiring schools to 'teach financial literacy' and 'teach digital literacy'. It's worth asking how these affect the teaching of actual literacy.

First, when you require that schools 'teach x', you're implicitly saying that it's okay if the kids can't read about x on their own, because you'll provide a teacher to do that reading for them, and provide oral explanations.

Education professionals call this meeting students where they are, but psychologists would call it enabling illiteracy. If you ever find yourself wondering how, in a district like Newport, 90 percent of kids can graduate, while only about 10 percent of them can read, this is how.

Second, there is an old saying that if you chase two rabbits, you won't catch either of them. By requiring so much content to be taught, while not actually requiring any of it to be learned — and by establishing no priorities — you're providing school administrators and teachers with a built-in excuse to ignore fundamentals in favor of incidentals. If 'learning about the Holocaust' and 'developing an awareness of and involvement with the natural world' are on the same level of importance as learning to read, you can guess how that's going to work out.

If you really have an opportunity to overhaul the Ed Rules, I implore you: Please use that opportunity to create rules that (1) focus on product rather than process, (2) are results-based rather than time-based, (3) prioritize goals, (4) recognize that producing autonomous learners is the goal of the enterprise, and (5) eliminate everything that can't be tied directly to the achievement of that goal.

In closing, I would ask that when creating those rules, you consider two crucial questions that almost never get serious consideration in discussions about education: First, if a kid wants to learn something, who can stop him? (And how much money do we need to spend to support that?) Second, if a kid doesn't want to learn something, who can make him? (And how much money do we waste by trying?)

I would also ask that you consider these questions in the context of the world of 2023, where high-quality, low-cost pedagogy is literally falling from the sky, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week — a world where a student in a school classroom has access to fewer resources, of lower quality, and vastly higher cost, than the ones available to him everywhere else.

Thank you for your consideration,

Ian Underwood

Croydon, NH

The Cardinal Choice

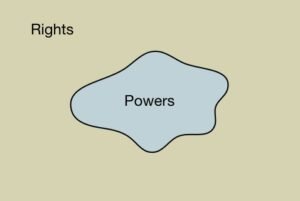

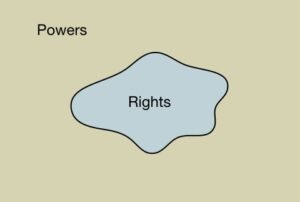

There are two ways of looking at the relationship between the rights of individuals, and the powers of government. The first, which is based on the ideas of the Declaration of Independence, is that people have the right to do pretty much anything, except when they delegate specific powers to government for the purpose of protecting those rights…

There are two ways of looking at the relationship between the rights of individuals, and the powers of government. The first, which is based on the ideas of the Declaration of Independence, is that people have the right to do pretty much anything, except when they delegate specific powers to government for the purpose of protecting those rights:

We might call the first view ‘Rights minus Powers’, or R-P for short.

The second, which has been steadily gaining traction, is nearly the opposite — government has the power to do pretty much anything, for pretty much any reason, except when that would violate some specific rights:

We might call the second view ‘Powers minus Rights’, or P-R for short.

To get a feel for the difference, consider the 4th Amendment. Under R-P, it means

We can’t search you, unless we can cite some specific delegated power.

Under P-R, it means

We can search you, unless you can cite some specific exemption in the form of a court-recognized right.

Note that the text of the 4th Amendment does create a specific delegated power: The government can search you if there is a warrant, supported by probable cause, and describing the specifics of the search. So under R-P, if there’s no warrant, there’s no search.

In practice, however, the government assumes P-R, grudgingly admitting that you have an ‘expectation of privacy’ which sometimes allows you to refuse to be searched, but increasingly often does not. So under P-R, a warrant is more of a suggestion than a requirement.

Contrast this with the 2nd Amendment, which creates no such delegated power. Under R-P, it means

We can’t prevent you from keeping or bearing arms, period.

Under P-R, it means

We can prevent you from keeping arms that we haven’t approved, and bearing them in situations that we haven’t approved.

In each case, the idea is that what is not permitted is forbidden. What differs is who is giving permission to whom. Under R-P, it’s individuals giving permission to government. But under P-R, it’s government giving permission to individuals.

That is, under R-P, rights are absolute, unless qualifications have been specified (as in the 1st, 3rd, and 4th Amendments). But under P-R, powers are absolute, unless specific exemptions have been approved.

These two views could hardly be more different, or have more influence on whether government moves towards or away from liberty.

I say ‘moves’ because over time, whatever is on the outside eventually crushes what’s on the inside. This is because everything on the inside is effectively an obstacle to be overcome.

In P-R, rights are seen as obstacles to ‘progress’, while in R-P, government powers are seen as obstacles to the enjoyment of ‘the right to be let alone’, which Justice Brandeis called ‘the most comprehensive of rights, and the right most valued by civilized men’.

In R-P, rights expand and powers shrink as the natural result of using improvements in knowledge and technology to relieve government of powers that it may once have needed, but no longer does.

In P-R, powers expand and rights shrink as the natural result of creating new exceptions, new entitlements, new emergency powers, new licensing requirements, and so on, all of which whittle away at the rights of individuals to control their own lives.

In short, the diagram for P-R is a picture of government by majority rule — where the Karenocracy™️ constantly looks for new ways to expand government power at the expense of individual rights, and people welcome this as a way of fleeing responsibility.

In other words, a world of children, with government as the parents.

In contrast, the diagram for R-P is a picture of government by consent — where individuals make their own decisions, reap the benefits when that works out, accept the consequences when it doesn’t, ask for help when they need it, and offer help where they think it’s appropriate.

In other words, a world of adults, with governments mainly providing peaceful alternatives to feuds and duels.

Of all the choices that we can make as a society, the choice between R-P and P-R is the cardinal choice, the one that determines, in the long run, whether rights eventually obviate powers, or powers eventually crush rights.

And it’s a choice that we have to keep making, over and over again. But to make the choice, we first have to be aware of the choice — between expansive rights limited by delegated powers, or expansive powers limited by approved rights.

Educability, Opportunity, & Necessity: The Keys to Fairness in Education

For students, fairness in education means: You get exactly the same adequate education as everyone else. No more, and no less. No matter who you are, or where you live, or what your parents can afford. And this takes as long as it takes.

For taxpayers, fairness in education means: Your taxes are used to pay for public benefit, but not for private enrichment, or political influence. And they are used to pay for results, not for time spent, or for good intentions.

What could be fairer than that?

[The following talk was presented in May, 2023 at the Annual General Meeting of the School Board Governance Association of New Hampshire.]

If we're going to make any significant changes to public schools, we need to change how we talk about public schools.

Right now, we talk almost exclusively about money, when we need to be talking about achievement.

The key to changing the conversation is changing how we think about fairness.

I've written a book about that. It’s called Rethinking Fairness in Education.

In this post, I’m going to use some ideas from the book to support some changes that we could — and should — make in education policy.

The first step towards shifting the conversation away from money is to realize that money is largely irrelevant. There are three graphs that make the case beyond any reasonable doubt.

The first graph speaks for itself. Over the course of half a century, we’ve tripled spending (adjusted for inflation), while getting no change in achievement — as measured by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), which is the test designed by the education establishment, to let us know how they’re doing.

The second graph is for the NAEP 4th grade reading test, but you can pick any test, for any grade, and it looks the same.

Each dot represents one state. Even though states spend anywhere between $7,000 and $25,000 per student, they all get about the same failing scores. The states with the highest scores like to say that they’re the best states for education. But really, they’re just the least worst.

The third graph shows the fallout from the Claremont state supreme court cases at the turn of this century. On the bottom, in blue, we see per-student spending by district before Claremont. On the top, we see the corresponding figures twenty years later, adjusted for inflation.

School spending increased everywhere by an average of $10,000 per student per year. Did I mention that that’s adjusted for inflation?

This means that every district is now spending more than any district (except Waterville Valley) was before. In terms of spending, every district is a rich district. But they’re getting the same results as before: less than half of students performing at the most basic level of proficiency in reading and math.

The message of these graphs couldn’t be clearer: Unless we change what we do, it won’t matter how much we spend.

And yet, the public policy remains focused on money.

The legislature is debating bills that specify how much schools need for 'adequacy payments’ — which are based entirely on attendance, and not at all on achievement, adequate or otherwise.

School districts are back in court fighting over spending amounts, and taxing mechanisms.

But before we can figure out how much we should spend on something, we have to know what we're trying to do, and why.

I suggest that to answer these questions, we take seriously what our state supreme court said in their Claremont decisions:

The why is to ensure the preservation of a free government.

The what is to provide each educable child with an opportunity to acquire the knowledge and learning necessary to participate intelligently in the American political, economic, and social systems of a free government.

It's worth noting that whenever I quoted the court at a Croydon school board meeting, it was greeted with cries of

That's a crazy Free-Stater idea!

That's too small a vision of public education!

That's detrimental to society!

and so on. As if it was something that I just made up.

When I quoted the court to a journalist, she accused me of being 'an originalist'. Regarding a decision from 25 years ago! The mind reels.

In a nutshell, I'm suggesting that we take the court’s statements at face value, paying careful attention to the words educable, opportunity, and necessary.

Educable has never been defined — not in a court ruling, not in a statute, not in an education rule. Whatever else we mean by it, we could make a good first step towards sanity by saying that ineducability includes 'refusal to learn'. That is, any kid should be able to declare himself to be ineducable, thereby relieving his school district of the responsibility to provide him with anything.

Any child — any person, really — who has a high-speed Internet connection and a computer or smartphone has the opportunity to learn pretty much anything that there is to know. So really, a school district could drop its school costs by a factor of ten or more by saying to each child in the district:

Here is your Chromebook ($300), and here is your Starlink subscription ($100 per month). Oh, and if your parents don’t have a better plan, you can enroll at the Virtual Learning Academy Charter School (VLACS) for free.

Before dismissing this approach out of hand, I would ask you to consider a couple of crucial questions:

If a kid wants to learn something, who can stop him?

If a kid doesn't want to learn something, who can make him?

We all know the answers to these questions. How different would our schools be if we took them seriously?

But even if we completely ignore educability and opportunity, we can still do something about necessity. If participating intelligently in the systems of a free government requires you to know something, or to be able to do something, then it is necessary — and the court says the state is required — to provide an opportunity to learn it.

Examples would include being able to read a statute or business contract or credit agreement, identify a specious statistical argument, understand when advocacy is being presented as science, tell the difference between an insurance program and a Ponzi scheme, and so on.

On the other hand, if participating intelligently in the systems of a free government does not require you to know something, or to be able to do something, then it is not necessary, and the state is not required to provide an opportunity to learn it.

Examples would include being able to speak French, spike a volleyball, play the violin, weld two pieces of metal together, calculate a derivative or integral, and so on.

We can think of illiteracy, innumeracy, and irrationality as three 'diseases' that would prevent someone from participating intelligently in the political, economic, and social systems of a free government. When considering whether taxes may be used to teach some knowledge or skill, we can ask: Which of these conditions does it help 'cure'? If the answer is 'none', then the state supreme court has placed it outside the scope of tax-funded education.

In the book, I show how this framework can be used to pare down the current laundry list that passes for a definition of ‘adequate education’ in the public school system.

But today, I want to present an even simpler approach, which we could implement with a couple of simple rules, based on taking the court's direction seriously.

Basically, if something is to be learned by any student, it must be learned by every student. Consequently, if something is not taught at every tax-funded school, it must not be taught at any tax-funded school.

For example, unless all tax-funded schools can put together a band, or a football team, or a robotics club, then no tax-funded school can have those. Unless all tax-funded schools can provide courses in welding, or AP History, or drama, then no tax-funded school can have those. And so on.

There are a few things to say about this, to prevent it from being 'interpreted' to just mean what we're already doing now.

First, we have to distinguish between teaching and learning. If something is necessary, then every student must learn it, and be able to demonstrate that learning. It’s not enough that a student just be taught it.

Second, by 'something', I don't mean nebulous categories like 'technology', where that translates in practice to some kids learning how to set up an Excel spreadsheet, while other kids are learning how to design and program robots.

(If all kids need to learn to set up spreadsheets — if that's necessary for intelligent participation in the systems of a free government — then that's part of the public school curriculum. If not all kids need to learn to make robots, then that's not part of the public school curriculum.)

I mean competencies, like being able to read a policy argument and identify the logical fallacies that are being used to mislead the reader.

Third, people often think that focusing on fundamentals is somehow 'lowering the bar'. Tell that to Michael Jordan, who famously said, ‘Get the fundamentals down, and the level of everything you do will rise’.

On the contrary, I’m talking about raising the bar, to the point where kids are literate, numerate, and rational enough to take charge of their own educations, and take full advantage of the torrent of world-class, zero-cost pedagogy that is literally falling, 24/7, from the sky.

I'm talking about teaching them the skills they need to learn whatever content they want, whenever they want.

That would be, not just a good first step, but a giant leap in the direction of fairness in learning, as opposed to fairness in funding.

But even if we continue to focus on money, there is something we could do immediately that would almost certainly cause significant improvement in student achievement.

In the real world, we pay for things after we get them. First, the tires go on, and then the installer gets paid. First, the tumor is removed, and then the hospital gets paid. And so on. This is so familiar to so many of us that it almost seems silly to mention it.

Schools don't work this way. But they should.

That is, schools should be paid, after the fact, for achievement, rather than beforehand, for attendance.

We already have precedents for this.

For example, VLACS only gets paid when students actually learn something. Proficiency first, payment second.

More interestingly, the current model for 'adequacy payments' is that schools get money this year for average attendance last year.

So the model is already in place. We don't have to change who we take money from, or who we give it to.

We just have to change what we're paying for. And refuse to pay when we don’t get it.

That is, right now, we pay for attendance, and get attendance — and not much more. What would happen if instead, we paid for achievement?

What if schools only got paid after the students learned what we need them to learn?

As I put it in the book,

For students, fairness in education means: You get exactly the same adequate education as everyone else. No more, and no less. No matter who you are, or where you live, or what your parents can afford. And this takes as long as it takes.

For taxpayers, fairness in education means: Your taxes are used to pay for public benefit, but not for private enrichment, or political influence. And they are used to pay for results, not for time spent, or for good intentions.

What could be fairer than that?

School funding: Who are the customers?

In the context of school funding, parents and students are not customers, as proponents of school choice programs like to proclaim. They are beneficiaries.

As of August 1, North Dakota no longer requires a license to carry a firearm, openly or concealed.

By now, this kind of thing is old news. The question is no longer 'Why wouldn't a state require a license to carry a gun?', but rather 'Why would a state require a license to carry a gun?' Or more precisely, 'What would give a state the idea that it could require a license to carry a gun?'

If you could go back 20 or 30 years to do some man-in-the-street interviews, how many people do you think would have predicted that by 2023, more than half of the states would operate this way?

As usual, the political change had to be preceded by a cultural change, a shift in perception. People had to stop looking at carrying a gun for self-defense as a privilege, and start viewing it as a right.

I just mention this because lately I've been having discussions with people who think of themselves as 'libertarian', but who balk at the idea that people would ever accept the following simple idea:

In the context of school funding, parents and students are not customers, as proponents of school choice programs like to proclaim. They are beneficiaries.

The distinction is crucial.

We collect taxes to pay for education because taxpayers are trying to purchase something that they need: A citizenry that can do things like read and understand a proposed statute or regulation; tell the difference between an insurance program and a Ponzi scheme; understand the difference, in a policy discussion, between millions and billions and trillions of dollars; recognize when an insidious proposal is being rationalized with a specious argument; and so on.

I’m not making this up. It’s right there in Article 83 of the state constitution, which says educated citizens are ‘essential to the preservation of a free government’ — in exactly the same way that Amendment 2 of the federal constitution says that armed citizens are ‘necessary to the security of a free state’.

Being educated, like being armed, isn’t an entitlement. It’s a responsibility.

Parents and children may benefit from this purchase, but it's the taxpayers who are making the purchase, for the reason cited above. As Confucius noted, the first step towards wisdom is to call things by their right names, and calling parents the customers in any school funding situation leads us 180 degrees away from wisdom.

A simple example can help illustrate the difference between customers and beneficiaries. Suppose I want my granddaughter to have the freedom to explore the area where she lives. She's not old enough to drive, so I'm going to buy her a bike. In this purchase, I'm the customer. She's the beneficiary. This purchase is about something that I want.

Which means that ultimately, I'm the one who is going to decide which bike gets purchased, and how much gets paid for it. I have a specific end in mind, and a specific plan for achieving that end.

In this situation, there are some things I'm not going to say to her:

Go pick out any bike you want, and I'll pay for it.

Here’s some money. I hope you’ll buy a bike with it.

Here’s a gift certificate that will be accepted by some nearby bike shops. Go buy a bike from one of them. If anything is left over, you can keep it, or spend it on something else at the shop.

Go pick out something you want, whether it's a bike or not, and I'll pay for it, up to a certain amount.

Each of them is analogous to some model of school choice as implemented in some state.

Now, she may have preferences, and I would encourage her to express those, and present her reasons for them. But ultimately, I'm the one making the decisions.

I (the customer) am buying something for her (the beneficiary) because I think it's important for her to have it.

Also, here's one thing I'm definitely not going to say:

Go pick out a bike, and I'll force other people to pay for it.

Note that as soon as we start thinking of parents as beneficiaries, and taxpayers as customers, a few things become obvious.

First, as beneficiaries, parents who can already afford to educate their children shouldn't be subsidized by people who can barely afford food, heat, and other essentials.

Second, as beneficiaries, parents don't get to call the shots about how the customers choose to spend their money. They can express their preferences, and argue for them, but ultimately, this purchase is being made by the taxpayers, for the taxpayers, for the benefit of the parents who can't afford to make the purchase on their own.

Third, the customers need to get what they’re paying for, which is not ‘what parents think is best for their kids’, but an educated citizenry, however they choose to define that. And if they don’t get what they paid for, then their money should be refunded — as it would be if they were purchasing other kinds of services.

Until we get this much straight — that taxpayers are the customers, and parents are the beneficiaries — nothing good or useful or sensible is going to happen with school funding, regardless of what kind of ‘school choice’ may get thrown into the mix.

In 20 or 30 years, will people look back at the idea that ‘parents are the customers’ when spending tax money taken by force from other people, the way they now look at the idea that you should have to beg permission from the state to be able to defend your own life? As a kind of temporary political insanity?

One thing is for sure. It won’t happen unless we start having that conversation now.

A Legislative Agenda for School Reform

With regard to education, I think that there are two broad legislative goals that we should be pursuing. First, to move school districts away from doing things that flatly contradict the written state constitution. Second, to move school districts toward doing things in the same ways that they are done in the rest of society.

With regard to education, I think that there are two broad legislative goals that we should be pursuing.

The first goal is to move school districts away from doing things that flatly contradict the written state constitution.

The second goal is to move school districts toward doing things in the same ways that they are done in the rest of society.

Consider the first goal. The written state constitution (in Article 83) recognizes that ‘free and fair competition in the trades and industries is an inherent and essential right of the people’, and requires the state to protect the people ‘against all monopolies and conspiracies which tend to hinder or destroy it’.

But isn’t this exactly what teachers’ unions do? Destroy competition in the industry of education by setting up a monopoly?

We should be pushing to remove any special status that unions have under the law, so that unions can form (like book clubs, or bowling teams), but can’t force anyone to deal with them.

Consider the second goal. Outside the topsy-turvy world of schools, you pay for work after it’s done, and only if it’s completed satisfactorily. You specify in a contract what will, and will not, be provided. If you’ve paid in advance, but the work turns out to be incomplete or defective, you get a refund. If you no longer trust the provider of a service, you’re free to seek out alternatives.

Only where schools are concerned do we find it acceptable to be forced to pay for something without even knowing ahead of time what it’s supposed to be; hope that we’ll get something we like; and acquiesce to returning to the same provider because it is able to maintain — with the state’s blessing and support — a monopoly.

The value of organizing legislative efforts under these overarching goals — which make up a mission statement, if you will — is that it gives some guidance about what we should be trying to accomplish, and how we should be looking to accomplish it.

For example, Article 83 requires the legislature to ‘cherish … seminaries and public schools’. Whatever cherish means, it can’t mean one thing for seminaries and something else entirely for public schools.

This suggests that a bill should be introduced to require seminaries and public schools to obtain public funding using a single, shared mechanism. What is forbidden for one would be forbidden for the other.

Or let’s look at special education. Here are two more bills that ought to be introduced.

One bill would require special education services to be provided via the same kinds of contractual agreements as services in the world outside of school. That is, the goals to be met must be spelled out ahead of time, in sufficient detail, using verifiable metrics, so that the asking price can be fairly evaluated; and refunds must be issued if the agreed-upon goals are not met.

The other bill would require repealing all truancy laws, in keeping with the state supreme court’s rulings in the Claremont cases that the state is responsible for providing the opportunity for an education to each educable child. It has no duty towards children who are not ‘educable’.

The term educable has never been defined. It needs to be defined. And that will be a long, contentious process. But we can start with this basic fact: You can’t teach anything to someone who doesn’t want to learn it.

A child who does not want to be in school is, by definition, not educable. So the state has no responsibility toward him, and no legitimate basis for forcing him to attend school. (I realize that this responsibility was invented out of whole cloth by the state supreme court, and is part of the oral constitution rather than the written one. But in this case, both constitutions agree: The state has no power to require anyone to attend school. Providing someone with an opportunity does not mean you can force him to take advantage of that opportunity.)

Are such proposals too radical? Think back to the early 1980s, before Florida passed its ‘shall-issue’ legislation concerning concealed carry.

Wouldn’t the idea that nearly all states would issue carry permits by default — and that more than half of them would drop the requirement for a permit— have seemed ‘too radical’ to be worth pursuing?

What seems radical at first becomes mainstream after enough conversation has ensued. The important thing is to get that conversation started.

As Wayne Gretzky used to say: You miss 100 percent of the shots you don’t take. There are thousands of small problems with the way schools are run, but I believe that the giant problems always come back to letting school districts get away with ignoring (1) the written state constitution, and (2) the lessons that we’ve learned about customer service in the world outside schools.

The Granhattan Project: 95% Literacy By 2030

One of the largest enterprises in New Hampshire is its public school system. What is the mission statement for this enterprise? Unfortunately, no one seems to agree on that.

For any enterprise to succeed, it has to take actions that will move it towards its goal. Perhaps more importantly, it has to say no to actions that won't do that.

This means it has to articulate a goal, in a simple, straightforward way, so that whenever it is contemplating a possible action, it can ask: Will this move me closer to the goal? If so, it's worth doing. If not, it isn't.

That is the role of a mission statement. It's a kind of guiding star, a way of deciding when to say yes, and when to say no.

For example, this is the mission statement of Southwest Airlines: 'To be the world's most loved, most efficient, and most profitable airline.'

Here was President Kennedy's mission statement for the space program: 'This nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.'

Simple, but not easy. Ambitious, but achievable. And very, very clear.

One of the largest enterprises in New Hampshire is its public school system. What is the mission statement for this enterprise? Unfortunately, no one seems to agree on that.

The more people you ask — legislators, judges, bureaucrats, parents, teachers, taxpayers — the more answers you get: To provide children with bright futures (college and career readiness) and pleasant presents (sports, hobbies, opportunities to socialize with friends); to create a workforce for employers (with subsidized daycare for employees); to allow us to compete in the global economy; to promote tolerance and inclusivity, and so on.

But the public school system does have a mission statement of sorts, at least on paper.

The state constitution is clear in saying that education is 'essential to preservation of a free government'. That's the why.

The state supreme court is clear in saying that it is the responsibility of the state to provide 'each educable child an opportunity to acquire the knowledge and learning necessary to participate intelligently in the American political, economic, and social systems of a free government'. That's the what.

The legislature has been clear in saying that 'schools shall ensure that all pupils are performing at the proficient level or above on the statewide assessment'. That's the how.

That last bit is buried so deeply — in RSA 193-H:2 — that you almost have to be Indiana Jones to find it. And it recently survived an attempt to repeal it, on the grounds that no one was really taking it seriously.

But what would happen if we adopted RSA 193-H:2 as the mission statement for our public school system? That is, what if New Hampshire embarked on what we might call the 'Granhattan Project', a program similar to the moon landing, or the development of the atomic bomb? A program attaching a real sense of urgency to a goal that is simple but not easy, ambitious but achievable, and very, very clear.

Something like: 'This state should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of bringing 95% of students to a 12th grade level of proficiency in reading.'

Note that in achieving this goal as a society, we would position students to achieve their own goals as individuals: To create their own bright futures. To attend college, or train for a career, or start a business. To learn more about whatever they want, whenever they want, for the rest of their lives. To be active creators, rather than passive consumers, of public discourse on subjects like tolerance and inclusivity — or taxes, or public health and safety, or criminal justice, or welfare, or any other matter of public policy. They would be able to participate intelligently in the political, economic, and social systems of a free government. And in doing so, help preserve a free government.

But we can only do this if we have a yes that is clear enough, and understood to be essential enough, to let us say no when we need to. To turn away from incidentals that distract from essentials. To follow our guide star, instead of veering after each new shiny bauble that appears on the horizon.

And if teaching every student to read is the wrong mission statement, let's come up with a better one.

How might we do that? One way would be to encourage stakeholders to make lists of all the things they think schools should be doing. Compile the lists, and see which items show up 95% of the time.

(It's the same basic idea as voting for the Baseball Hall of Fame, but with a higher threshold.)

The idea is to find consensus, in order to avoid contentiousness; to cooperate with our limited resources, instead of competing for them; to pull together in a common direction, instead of pulling in a dozen directions at once. To chase just one rabbit, and catch it, instead of chasing a dozen and missing them all.

Zig Ziglar expressed the idea behind a mission statement this way: 'You can’t hit a target you cannot see, and you cannot see a target you do not have.’ And even more simply: ‘If you aim at nothing, you’ll hit it every time.’

I have yet to see a more accurate description of our public school system. We can do better, and we need to do better. A great first step in that direction would be embracing RSA 193-H:2, instead of eliminating it, or continuing to ignore it.